-

Magazine

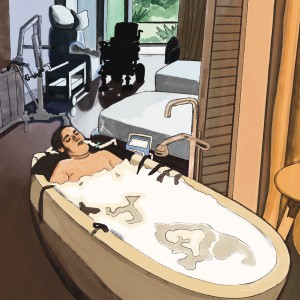

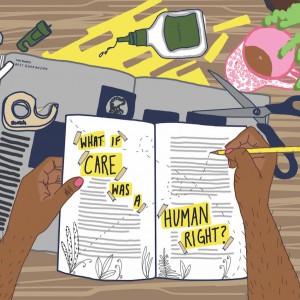

MagazineDreaming of home care futures

Without a public home-care system, disabled people are forced to choose between living in a long-term care home, medical assistance in dying, and hiring an underpaid migrant home-care worker.

-

Magazine

Magazine“There are disabled people in the future”

An interview with Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha about “crip doulaing,” the future of the disability justice movement, and understanding access and care as joyful.

-

Magazine

MagazineDisabled leadership and wisdom

When we say we want disability justice, we don’t just mean wheelchair-accessible buildings and sign-language interpretation. We mean an end to the systems and structures that disable and debilitate us and a future where there is enough care, community, and support for everyone to thrive.

-

Magazine

MagazineThe slow crisis in Saskatchewan’s long-term care

Though 80 per cent of Canada’s COVID deaths have happened in long-term care homes, Saskatchewan has fared better than the Canadian average. It was thanks, in part, to its relatively robust system of publicly owned homes. But in recent decades, cracks have begun showing in that system.

-

Online-only

Online-onlyMigrant workers are the present and future of low-carbon care work

Migrant workers are keeping us alive through catastrophes like COVID-19, but they face an impossibly complex, punitive, and high-stakes immigration system. It’s time to completely overhaul the way we value those who do the most vital, life-giving work.

-

Magazine

MagazineThe labour of care

When the pandemic took hold in March, the nature of my work as a doctor in remote communities in northern Quebec and Ontario changed drastically. The practice of medicine is defined by coping with uncertainty, but few had experienced the scope of the ambiguity through which we lurched.

-

Magazine

Magazinelove as radical action

What does it mean when “choosing love” isn’t an individual act, but a collective effort of building a world in which all of our material needs are met? estefania alfonso falcon reviews Kai Cheng Thom’s I Hope We Choose Love.

-

Magazine

MagazineTransformation takes practice

There’s no rulebook for transformative justice work. What we have and are being given are principles, beliefs, guidelines, and personal experiences. We must use these offerings iteratively, as tools to grapple with our own spaces and our positions within them.

-

Magazine

Magazine“They take my labour, but not my family”

The federal government is ending the Caregiver Program, which gave migrant caregivers a pathway to permanent residency. But caregivers are fighting back by demanding permanent residency upon arrival.

-

Online-only

Online-onlyWe don’t need to be friends to be comrades

To ask activist groups to take on responsibility for members’ emotional well-being is to saddle them with an impossible burden – something that makes activist burnout more likely.

-