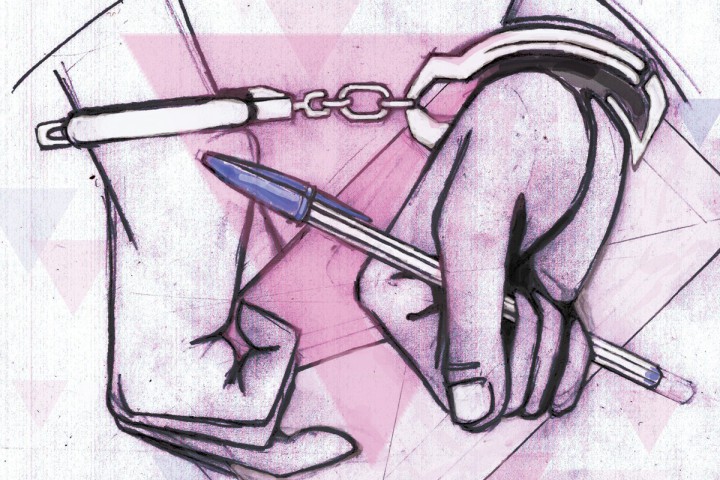

COVID and sexism in a women’s prison

My name is Tamina Hamid. I’ve done 15 years on a capital aggravated life sentence in Texas, and I have 15 more to go.

Texas prisons are made for men. The jobs, training, clothes, and parole are all designed for men. Take, for example, the Texas 7: in 2000 seven male inmates broke out of a Texas prison. They had all been classified as trustees – prisoners who were given special privileges and responsibilities for good behaviour. After their escape, the rules around classification changed for everyone, even though no women were part of the escape.

Women do not get nearly the same job opportunities that men do. I’m not made a priority for schooling of any type, and I have to work twice as hard to get the privilege of a good job. What’s a good job? Well, for women, there’s not much. Maybe a maintenance job or, oh … that’s about it. I can barely get a job that will give me on-the-job training, which would let me earn a technical certificate while on a work assignment. I currently work as a bar screen, where I rake trash in an open sewage system. Where is that sewage disposal training really going to take me? I do not earn good time or work time – hours of work or good behaviour that count toward parole. But it matters what your classification level is: if you currently or previously have an aggravated charge, like I do, you get neither good time nor work time.

I currently work as a bar screen, where I rake trash in an open sewage system. Where is that sewage disposal training really going to take me?

Women are defeminized in prison. We are not allowed to have clothes that fit tight, or wear too much makeup or glitter. Officers tell us not to do our hair. We are made to wear men’s clothes and shoes. Commissary has few items that are girly or have feminine scents. Women have few cellphones or drugs, but you know what these girls love? Eyeshadow!! OMG!! Lock it down!

In prison, women do not have contraband cellphones like men. In 15 years, we’ve only had two on the Lane Murray women’s unit. During the COVID pandemic, it was men with cellphones who could take pictures of our johnnies (the brown bag lunches that usually hold meat or cheese or peanut butter sandwiches) and send them to the Marshall Project, a prisoners’ rights organization, so they could step in to address how we were being fed. They did that to let the outside know about the abuse we face and the poor quantity and quality of our food during the COVID lockdown.

Prison is a lonely place, but being a woman inside makes it even lonelier. I don’t have children to miss and I’m not close to my family. Being a woman in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) without the opportunity to get the training and job opportunities that men do feels degrading and sexist. We watch the world empower women, but behind the razor wire we have no power to fight for ourselves. This is not just because it is a man’s world in here, but also because women turn on each other. We cannot find common ground. We don’t know how to unify. When I fight for more job training opportunities, classes, and programs, I often wonder if I am fighting for those of us who are staying in here or for those being released. Is it even worth the fight for those who are released? But then again, isn’t that the point of giving us women a fighting chance?

We watch the world empower women, but behind the razor wire we have no power to fight for ourselves. This is not just because it is a man’s world in here, but also because women turn on each other.

We have no voice. When we file grievances, they are ignored by our unit. When they are escalated, these higher-ups ignore protocol, procedures, rules, and footage. “No evidence” – that’s what they like to say when we file grievances. I am one of the women who has been fighting for change. I’ve been retaliated against and blackballed. I still keep going.

Being in prison has given me PTSD, anxiety, and deep depression. Then the COVID pandemic struck! Now we’ve done over a year of COVID lockdown.

The pandemic was slow to hit TDCJ. At first, no one was taking it seriously. Then we got lockdowns: we were told to remain in our cubicles or locked in cells 24 hours a day. No dayroom, no outside rec, nothing. Some officers wanted to limit how many inmates were in the restroom area. We were fed barely edible johnnies. To “sanitize” the facilities, the prison officials spray chemicals with unknown long-term effects. Only TDCJ thinks keeping us locked down in our cubicles is social distancing – we live on top of each other, even when locked down. Because of COVID, there is no recreation, no socializing, no visits. We are cut off from our families. The little bit of life we were allowed in here has been taken from us. We hold our breath during testing, hoping that with no positives we’ll have a chance to use the store.

The TDCJ’s COVID policies are enforced by guards, who punish prisoners who disobey. I was harassed and threatened for putting lotion on my face. I grieved it to no avail. Policy is ignored because I am an inmate.

When we file grievances, they are ignored by our unit. When they are escalated, these higher-ups ignore protocol, procedures, rules, and footage.

Every day I wake up with anxiety about who our officers will be. Are we getting a hater or not? Will the rules change today? What will the TDCJ take from us today? They have taken away on-the-job training positions – day operator, support service inmate janitor, counter attendant, and more. These changes might not be significant to anyone but us, but women have struggled to get what little we have in here.

Every day I deal with officers’ abuse of their authority. Every day is something new. One day, they want to take disposable masks away from everyone who has them. The next day, they take all the homemade masks. I know they don’t wash our masks daily but not wearing one is dangerous. Shouldn’t the officers be happy we’re wearing them?

COVID has produced a lot of different opinions in here. Some believe in it. Some don’t. That’s officers and inmates alike. There are officers who don’t wear masks around each other but then act like we are diseased. They brought it in to us. They love to threaten us, but they don’t follow policy themselves. I documented the fact that officers weren’t wearing masks or other PPE, and I filed a grievance about it. I was called to the warden’s office and told I should have told ranking officers instead of filing a grievance with the ombudsperson.

These changes might not be significant to anyone but us, but women have struggled to get what little we have in here.

COVID has strained our mental health. We have become hoarders of food and soap. We are short-tempered. We have gone without mental or physical exercise due to being confined to our cubicles or cells. No games, inside or out. The TDCJ has crowded us in here. In my pod, there are 102 of us. Eighteen tables that used to seat four are now one per table. I personally had to save my own mental health. I started working out and made my own weights.

TDCJ did not and does not care about my mental health during the pandemic, so I struggle with anxiety and depression all on my own. I have to fight my inner demons by myself. So here I sit, hoping that I have given you a glimpse of life we struggle with. It will get worse before it gets better.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.

_720_480_90_s_c1.jpg)