Criminalizing the sex trade does sex workers no favours

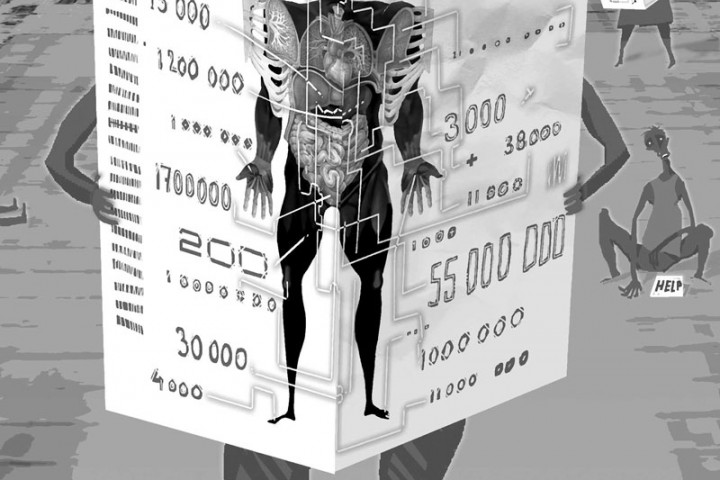

At some point in one’s life, every adult human being is valued for an isolated skill, talent, or personality trait—and compensated summarily. Most of the time, it’s called “gainful employment.” But if you happen to work in the sex industry, it’s often called “objectification”: a loaded term with unpleasant—and sometimes unfair—associations.

In the 1980s and ’90s, sexual objectification became synonymous with “exploitation” when anti-porn feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon sought to vanquish the evil porno empire by shutting down smut shops once and for all. Many Canadians will recall the 1992 case of R. versus Butler, in which pornography distributor Donald Victor Butler was forced to close his adult boutique in Winnipeg because of a Supreme Court ruling that drew heavily from Dworkin and MacKinnon’s definition of obscenity. The final ruling was initially deemed a triumph for womankind, though the case was ultimately a pyrrhic victory—one that divided the feminist community into two opposing camps: anti-porn, and sex-positive. However, this marked division did little to further the overarching goals of the feminist movement. Indeed, the old adage “united we stand, divided we fall” characterized the aftermath of the R. versus Butler ruling. The impassioned division still remains today, and continues to inhibit progress on feminist issues—particularly where those issues intersect with the sex industry.

While there are serious, identifiable problems with the sex industry, the actual act of sex itself is surely the least of these problems. In fact, many feminists’ moralistic fixation on the sex in sex work has actually made it more difficult for sex-workers’-rights activists to improve the work conditions of these workers—at least some of whom, it is worth pointing out, actually enjoy their work.

Just because the “service for sale” happens to be a few minutes of steamy lap dancing or an hour of intimate companionship instead of a week’s worth of memo typing, hamburger flipping, or taxi driving shouldn’t automatically negate the worker’s sense of self-worth and agency. In fact, many successful sex workers point to other occupations (waitressing, housekeeping, even teaching and computer programming) as vastly unfulfilling when compared to sex work.

Norma Jean Almodovar, director of COYOTE-LA (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics-Los Angeles) and author of Cop to Call Girl, noted the following in our recent interview: “When I became a call girl, it was just such a different mindset—instead of making people’s lives miserable, I was making them happy. I was giving them pleasure. People looked forward to seeing me, as opposed to when I was on the police department, when people did not look forward to seeing me!”

While it’s marvelous to hear the oft-ignored voices of happy, healthy sex workers, it’s important to remember that some sex workers suffer fates far worse than “objectification.” Some are abused or even murdered by their pimps or their tricks, some succumb to drug addiction, and some contract sexually transmitted infections. But criminalizing prostitution has done little to alleviate these tragedies—if anything, by pushing marginalized women and men into the least-regulated work environments possible, it has aggravated them.

In New Zealand—one of the many progressive nations to decriminalize prostitution in recent years—prostitutes now have access to free medical clinics, discounted safe sex supplies, tax assistance, drug counselling, and regularly updated booklets with photographs of customers to avoid. Brothels are frequently inspected to ensure that they comply with strict hygiene requirements, verify each sex worker’s age with government-issued identification, and protect employees against harassment. Sex workers have professional advocates to turn to should they wish to seek legal recourse against an exploitative boss. There’s even talk of forming a prostitutes’ union.

It is, in short, a model of how the sex industry ought to operate—a system in which the “bad” pimps and prostitutes are penalized through a legitimate judicial system, while the “good” ones are allowed to go about their business of providing pleasure in the safest environment possible. It’s difficult to object to that.

A.E. Franzen is an aspiring dandy based in Minneapolis who writes smut for fun, news for pay, and op-ed pieces for ski lift passes.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.