The lineage of care

Notes on the outsourcing of family obligations

My mother is a caregiver. For hire, she will be you if you are too busy to be you, because she needs the money to continue being some semblance of herself. She has no professional training. She is not a nurse or a doctor, and she’s not allowed to give prescription medicine – just care, car rides, baths, home-cooked meals, changes of clothes, and companionship.

My mother is a caregiver. If you cannot go near your own waning mother to feed her because she will bite you, hire my mother. She will be bitten on your behalf, for the bank, for the phone company, for dollar-store groceries, and will feed herself to a system that has not fed her. When she gets home and feels the grass in her front yard tickle her knees and finds a notice from the town penalizing her for not keeping the armies of grass as trim as those of her neighbour, it will be because she was busy shepherding the last breaths from the generation that believed most in lawns.

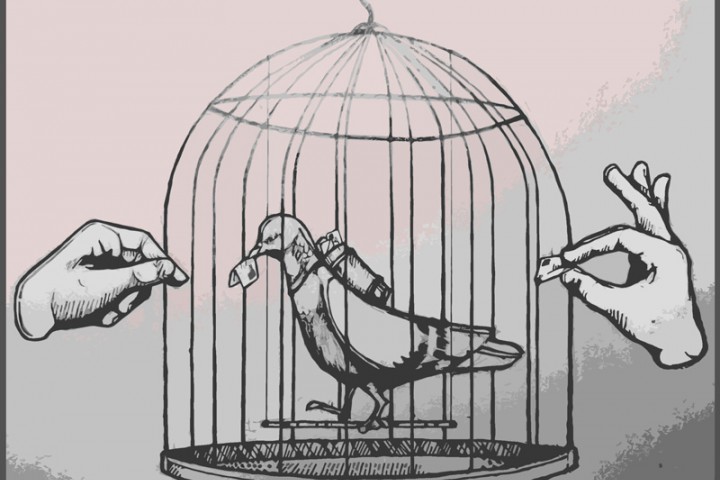

My mother is a caregiver, and has been for 15 years, in an industry created by the outsourcing of family obligations. Having created the problem of busyness, the capitalist market must sell solutions that make it easier for us to be busy. But with every responsibility that we subcontract out, we become less and less our own people, until we are nothing but slivers of ourselves littered across the intersection of the division of labour and the division of family.

This is where my mother works, cleaning up the slivers of intimately known strangers. Yet, as I approach my 30s and my mother grows closer in age to the people she takes care of, I age into the same question that has confronted each of her clients: how will I take care of my parents when they need me to return to them some of the care they gave me when I was young?

As it is, we live on opposite coasts, connected by weekly phone calls. “I want out, Khristopher,” she says. “I’m tired. My knees are killing me. I can’t sleep straight on my back. I keep forgetting everything. I’m about to lose another tooth, but I can’t afford to get it looked at. I don’t have time to make any food for myself anyway.” It’s been the same since she began working as a caregiver while I was in high school, when the calls came from someone else’s living room where she was “on an overnight,” sometimes for multiple nights each week.

The calls usually end with what is, to me, the most wrenching part of the script. “It’s hard. I love my job. I do. These old people, their stories. And I think I’m pretty good at it.” My mother genuinely enjoys caring. But because her care is commodified, the value of her passion is limited.

Outsourcing and institutionalizing our fundamental obligations can’t fully exempt us from them. Eventually, those who work as professional caregivers can no longer hold the responsibility that’s been passed off to them; they need to be cared for themselves. But as a low-wage worker who hasn’t been able to keep most of the money she’s made, my mother can’t hand off her own care to a hired helper like herself.

For sons and daughters who find themselves at this transitional moment, holding this beautifully inescapable burden, it ought to be refreshing to remember that in an age of disposable culture we cannot discard our obligations to our elders. By making commodities of the intangible, foundational elements of our humanity, like caring for our parents, the market has transgressed into realms more intimate than simple “stuff.” We should pause and look into the consequences of convenience. There is a richer future to be had by rescuing the inconveniences of life that make us human. Without them, we will sail the oceans of individual liberation only to drown in a sea of self-abandonment, with no time-tested tethers like family to save us. Perhaps capitalism will invent another rope to throw us. But don’t be surprised if it wraps around your throat and pulls you up by the neck.

Personally, I would rather count on what I already have: my own ability to offer care to those who come before and after me. As challenging as it is, making myself available to care for my mother as she ages is both a stabilizing intervention against the indefinite appetite of capitalism and the wisest investment I can make in my own future – the continuation of a tradition of caring that’s more private than privatization can grasp.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.

1 Comment

Socializing elder care work as paid employment should not be seen as a negative development. This type of engagement should be viewed as an obligation of the community and not of individuals who are connected by blood or fictive kinship ties.

The community has a social responsibility to help the elders whose labour it once used its perpetuation. It is now the collective’s time to take care of the elders at this stage of the life cycle.

The exploitation of the labour of care workers is something that will end with the demise of capitalism and labour alienation. However, we must continue to fight for better wages and working-condition for personal support workers and other workers who engage in in-home and institutionalized care of the elders.

I am a partisan of the outlook that calls for the “abolition” of the family, as we know it, and socializing almost all forms of social reproductive labour (done outside the home as paid work).

From Ajamu Nangwaya in Toronto on Jan 4th, 2014 at 3:54pm