Tuition Freeze 100

Across the country, two provinces stand out for their accessible post-secondary education systems. One is Quebec, where the vigorous student movement routed efforts by the Charest Liberal government to increase tuition fees by 84 per cent over seven years. The other is Newfoundland and Labrador, where student activism has been only sporadically intense and yet, at least ostensibly, equally successful. The comparison between the two provinces is not straightforward, given that Newfoundland’s out-migration problem gives politicians added incentive to keep education affordable. The province has consistently low tuition fees and a system of up-front, needs-based grants that has replaced student loans. Full-time undergraduate tuition at Memorial University, for example, is a mere $2,550 per year, and all outstanding loans have been interest-free since August 2009. What’s more, tuition fees have not risen since 1999, when protests forced the hand of Brian Tobin and laid the groundwork for a fee reduction under Roger Grimes in 2001. “Students made it impossible for me not to freeze tuition fees,” former premier Tobin had said.

The numbers

Newfoundland is in a challenging fiscal situation. Like Quebec, Newfoundland receives federal transfer payments to assist with the cost of post-secondary education. In 2008, the province stopped receiving equalization payments; as of early 2016, it must start repaying a federal loan made to offset losses when the equalization formula changed. The politics of equalization payments have long been contentious in Newfoundland, reaching peak pressure when Progressive Conservative premier Danny Williams accused Stephen Harper of betraying the province and breaking his word over the exclusion of non-renewable resource revenue from the equalization formula. Now, repayment of the loans is sure to strain the province’s next budgets.

It is perhaps fortuitous for students, however, that Newfoundland and Labrador has an unusual socio-economic situation that makes politicians receptive to students’ lobbying: the province has an aging and sometimes fleeing population. Importantly, Newfoundland’s economic history and cultural memory is marked by the imposition of a moratorium on the cod fishery in 1992. The fishery had been the economic lifeblood of Newfoundland and Labrador, once sustaining entire communities and regions that have since suffered dramatic, sustained population loss. While the pace of out-migration, particularly by young adults, appears to have slowed down or stabilized in recent years, Newfoundland and Labrador has the lowest percentage of youth among all provinces; these demographics indicate a long-term policy concern.

In 1992, the province’s population was just over 580,000, and it declined successively for years after. The Newfoundland & Labrador Statistics Agency pegged the province’s population at 527,000 in 2015, up from a low of 509,000 in 2007. Out-migration has hollowed out Newfoundland’s tax base and caused the rapid aging of small communities, many of which are disappearing. The generational traditions of living and working around the fishery are dying, and community-based identities have changed forever. It’s clear to the provincial government that Newfoundland needs to retain young adults or risk a situation that could quickly turn desperate.

Student strategies

Newfoundland’s status as an outpost of accessible education is the product of a movement that has chosen diverse strategies – partly because it has never been as decisively threatened as Quebec’s student movement was in 2012. The student movement’s tactics include not only lobbying and research, but also selective use of demonstrations and, often, a rather conciliatory stance that frames student interests as mass public interests.

Critically, it has also built relatively diplomatic relations with the provincial government that, in recent years, has produced incremental improvements, culminating in what former premier Williams called in 2007 “the best student aid package in the country, the envy of students everywhere.”

Michael Walsh, the former chair of the Canadian Federation of Students’ component in Newfoundland and Labrador (CFS-NL), is among those who have emphasized student unity as part of the reason tuition fees are low. The province remains the only one where all public post-secondary student unions are part of the Canadian Federation of Students, the largest student organization in Canada, which lobbies the federal and provincial governments on education issues.

“The victories of the student movement in Newfoundland and Labrador have been as a direct result of our unity,” Walsh told Socialist Worker in April 2014.

“Sometimes students in other parts of Canada look to the example from Quebec and think that mass strikes are the key to achieving our goals, but in [Newfoundland and Labrador] we have won the lowest tuition fees in the country and the elimination of provincial student loans without sustained strike action,” Walsh said.

Walsh’s successor, Travis Perry, echoed the importance of student unity. “When we meet with government, we are speaking on behalf of all public post-secondary education students in the province. It’s a unique thing in the country and it often forces the provincial government to listen to us. But we also take a three-pronged approach to any campaign,” he said, referring to lobbying, research, and organized action.

Elsewhere in Canada, students have disaffiliated (or attempted to disaffiliate) from the CFS in raucous disputes. Some, like student politics writers Titus Gregory and Adrian Kaats, argue that the CFS is overly bureaucratic. More commonly, de-federation campaigns frame the CFS’s social justice orientation as irrelevant to student interests. David Bush of RankandFile.ca, in a piece published on rabble.ca titled “Think before you blow up the CFS,” perhaps best articulated the view that the CFS, whatever its faults, has a clear net benefit for the wider student movement. Students of the left, he argues, who seek to address legitimate problems of the CFS, like the heavy bureaucracy, unaccountability, or financial mismanagement, are short-sighted if they ally with the right to de-federate individual unions from the CFS. Individual student unions that leave the CFS, even with hopes of becoming more radical through their independence, risk weakening themselves through isolation.

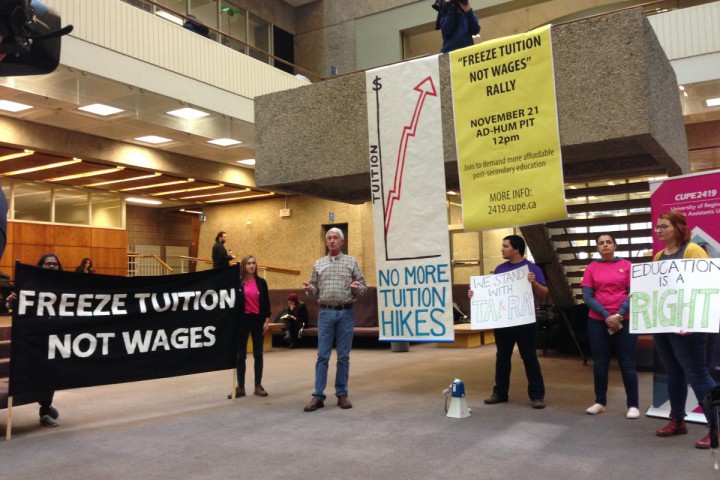

While these tensions and debates flare up on campuses across Canada, student union leaders in Newfoundland are united with the CFS, says Hesam Hassan Nejad, a PhD student at Memorial University and the communications director for its graduate students’ union (GSU). We discussed a demonstration that occurred in June 2015, when, in a relatively rare moment of confrontation, students protested the release of the province’s Population Growth Strategy, a policy aimed to improve the province’s population challenges by incentivizing immigration and workforce development. As Nejad recounted, the timing and focus of the strategy angered students: it came less than two months after the government announced cuts to Memorial University’s funding, prompting students to feel betrayed by then-premier Paul Davis’s apparent dismissal of accessible education as a path to a demographic boost.

The Population Growth Strategy was already facing criticism from opposition parties for having too few specific targets and goals to measure the strategy’s impact. But students were also able to show that it was hypocritical. Memorial University had proposed that it would increase tuition fees for international and graduate students, despite a report by the university’s faculty of education researchers showing that the low fees were a major incentive to move to Newfoundland, particularly for students from other parts of Atlantic Canada.

“They failed to acknowledge the important role that post-secondary education plays in growing our population,” Perry said. Shortly after the demonstration, Memorial University reversed its plan to hike tuition fees for international undergraduate students. Plans to increase fees for Canadian and international graduate and medical students’ tuition, as well as residence fees, were delayed by a year. Perry sounded even-minded about the impact of the activism.

“We’re definitely going to be doing a lot of work leading into the provincial budget this year. We did achieve some victories with actions that we took last fall,” he said. “But there’s still a lot of work to be done.”

The political climate

The student movement in Newfoundland is also attuned to the province’s political climate. Newfoundland and Labrador has a fairly exclusive political class that exerts disproportionate influence over the wider society, and the province’s powerful business class is enmeshed with the pool of government leaders. Convincing this narrow group that student interests are part of the wider public interest has sometimes taken unusual turns.

In 2007, on the steps of the Confederation Building, students presented then-premier Williams with a petition highlighting the role of debt in driving students out of the province. Williams, admitting that the province was indeed losing young people to student debt, “was so forceful on the issue,” the CBC reported, “that he sounded like one of the demonstrators himself.” Williams’ government introduced up-front provincial grants for students and his successors eventually replaced the provincial student loan program altogether, helping to make a significant dent in many students’ debt loads.

While Williams’ fiery charisma was never matched by successors, former premier Kathy Dunderdale was able to approximate his ability to appear to be on the side of students. Notably, she and then-advanced education minister Joan Shea spoke at the CFS-NL’s Day of Action in 2012.

“I wouldn’t have been able to come to university without the support of student loans…. I agree with Jessica’s statement,” Dunderdale said, referring to Jessica McCormick, the CFS-NL chair who preceded Walsh. “Education is a right, not a privilege.”

In 2011, the CFS launched a campaign to present Shea with 15,000 signed postcards appealing for the retention of the tuition freeze. Two years earlier, Shea personally accepted a stack of petitions from CFS and its locals in the Confederation Building’s lobby.

Amid these iconic episodes of engagement with premiers and education ministers, more creative tactics have also been part of students’ repertoire. “Sometimes we’ve collected valentines calling on the premier to maintain the tuition fee freeze,” Perry said.

Referencing_ The Simpsons_ character Lisa Simpson’s valentine to Ralph Wiggum, students in 2012 sent appeals to then-federal Conservative Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development Diane Finley that read, “I choo-choo-choose you … to reduce student debt.” Students were seeking federal investment in post-secondary education.

In November 2015, students stood frozen in place on Water Street in downtown St. John’s, baffling onlookers. It was meant to appeal to party leaders to “keep the freeze” on tuition fees in place.

International student tuition

Nonetheless, the future of education accessibility in Newfoundland remains tenuous. Though Nejad and Perry expressed that the Liberal government, elected by a landslide in October, has been more communicative than the previous government, Premier Dwight Ball has only committed to maintaining a tuition freeze for students who are residents of Newfoundland and Labrador. Students from outside Canada or from other parts of the country will almost certainly face tuition fee increases.

In the past, members of Memorial University’s student union have protested the disparity between Canadian and international student fees, while a university-authored report opined that Memorial has many areas for improvement when it comes to serving international students generally. At a protest in May of last year, Bangladeshi student Tamanna Khan said that backtracking on the current tuition freeze would hurt her family’s already-fragile finances and would contradict what she was told by recruiters.

“When I came in here in 2013, the recruiters of the MUN [Memorial University of Newfoundland] told me that the tuition is going to be frozen for my whole degree,” she told the CBC. “When I see the tuition fee is going to be increasing, my mother back home, she is scared. She can’t afford that for me.”

Memorial University of Newfoundland Students’ Union (MUNSU) director of student life Brittany Lennox also expressed her view that the current two-tier system was unjust, while connecting the issue to the province’s out-migration problem.

“If prospective students lose faith in the commitment of our province and our university to that tuition fee freeze, then we will lose the important opportunity to build our economy and help our province recover from the economic and population crisis that it is facing right now,” Lennox said to the CBC.

“Not only that, but international students already pay upwards of three to four times [what] Canadian students [pay] for the same education. We just want to point out the system that we … have is already an awful form of discrimination.”

The future of low tuition

In February, the CFS-NL’s annual general meeting set the stage for future work. The protests and lobbying that led to the tuition freeze’s introduction in 1999 are basically now only an abstraction for most of the participants: Perry and his fellow students were children at the time that current provincial education minister Gerry Byrne was a federal MP representing the northern and western parts of the island.

“I’m hopeful. We’re going to be pushing for it,” Perry said, referring to the retention of the tuition freeze for non-Newfoundland residents. “We’re going to have a conversation with Minister Byrne and see where that takes us.”

Much has changed since this article was written. On April 14, 2016, Newfoundland and Labrador’s new Liberal government introduced its austerity budget, which cut $8.3 million from Memorial University’s operating costs and $3 million from the university’s salaries. The government also partially re-introduced student loans. Grants are now also eliminated for students who choose to study outside the province, unless their chosen program is not offered in Newfoundland. Travis Perry and national CFS chair Bilan Arte said that they were caught off guard and are shocked by this decision. Widespread discontent over the budget is spurring a wave of protests across the province. When Gerry Byrne, Minister of Advanced Education and Skills, tried to justify austerity measures, he was shouted down at anti-budget protest with calls to “tax the rich.” Students have participated in these rallies, which show no sign of slowing down. The demonstration on May 7 is expected to be the largest yet.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.

_720_480_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)