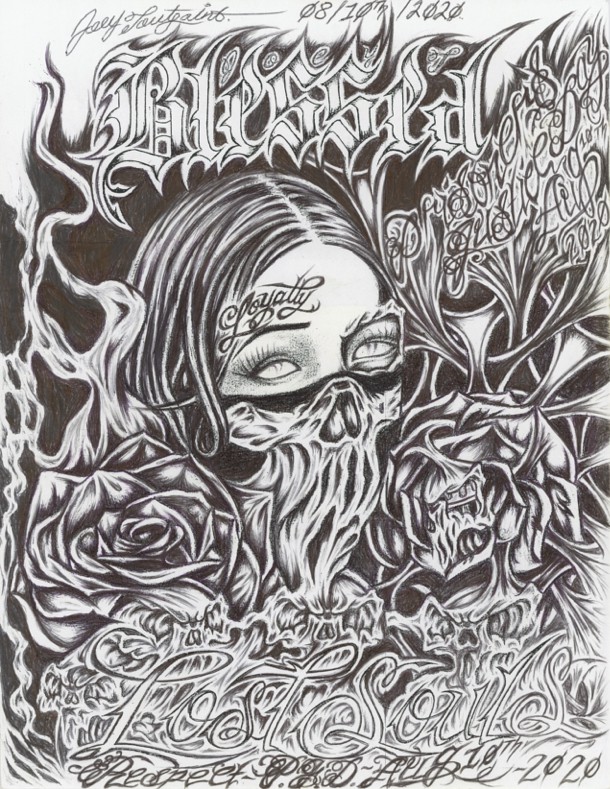

One less prison to be torn down

On June 18, 2019, I was paged to the counsellor’s office to pick up legal mail. Receiving legal mail is a routine part of prison life. You show the counselor your identification card and sign for your mail, while they slice open the envelope and check for contraband. In and out in a matter of minutes. On the walk back to my housing unit, I pulled the letter out for a quick glance. I will note that the legal mail I usually receive is fairly mundane. As I read, I stopped walking. This time was different.

I was holding a letter from my attorney informing me that the Record of Decision for a proposed United States penitentiary and federal prison camp in Letcher County, Kentucky, was withdrawn by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). With the Record of Decision withdrawn, those prisons were not going to be built anytime soon. We had essentially won – something practically unheard of against a behemoth like the BOP.

Having outside help made this project possible, because organizing in the BOP is very difficult these days.

This was the culmination of a project that began several years earlier, when the BOP failed to provide notice to the prison population of the proposed prisons. By not providing access to the Federal Register and the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), the prisoners housed in BOP facilities were not able to meaningfully participate in the required public comment period. BOP prisoners would be directly impacted by the proposed prisons because they could potentially be housed in them. Participation in the public comment period would have allowed BOP prisoners to have their voices heard. These actions by the BOP violated the National Environmental Protection ACT (NEPA) and the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). Subsequently, these NEPA and APA violations became the basis of a class-action lawsuit filed by 21 prisoners (including me).

Prior to the actual filing of the lawsuit, the 21 BOP prisoners (again including me) were required to exhaust all available administrative remedies. My personal experience with the Administrative Remedy Program was silence on the part of the BOP. I began with a simple request to the legal department for a copy of the EIS and any information in the Federal Register regarding the proposed prisons. No response. I then filed a request with the warden asking for the same documents. No response. I filed an appeal to the regional director, once again asking for the same documents. No response. Finally, I filed an appeal to the general counsel asking for documents. No response. At that point, I had exhausted all available administrative remedies. I could now seek relief in the courts. I had standing to be a plaintiff in the lawsuit.

BOP prisoners would be directly impacted by the proposed prisons because they could potentially be housed in them.

There was an interesting organizing component to this lawsuit: the attorneys and the law students. They were the key to organizing 21 geographically diverse prisoners housed in separate BOP facilities across the United States. Having outside help made this project possible, because organizing in the BOP is very difficult these days. Clubs and groups, which used to be common, are no longer allowed. In fact, the BOP has four specific prohibited acts that directly address prisoner organizing:

212 – Engaging in or encouraging a group demonstration.

213 – Encouraging others to refuse to work, or to participate in a work stoppage.

315 – Participating in an unauthorized meeting or gathering.

336 – Circulating a petition.

Get caught violating any of these and the most likely result is a trip to segregation, also known as the special housing unit or “SHU,” and a transfer to a higher security facility.

As a plaintiff in the lawsuit, I worked directly with an attorney and two law students. They were located in New Orleans. I was housed in a federal prison camp in Florence, Colorado. I sent them regular updates as I worked my way through the administrative remedy program. In return, they sent me the latest news articles and documents about the proposed prisons. We communicated through legal mail to reduce the chances that prison officials would interfere with our communication, but it did not eliminate the risk entirely. On several occasions, letters sent through legal mail were withheld from me for several days. When I inquired about why this was happening, I was told that I was paged earlier, but that I never showed up. Aside from the legal mail delays, I did not endure any major retaliation from prison officials. Being involved in litigation against the BOP can open the door for retaliation by prison officials. Is this something that should happen? No. Does it happen? Of course. I believe I was spared largely because I was litigating a couple of proposed prisons on the other side of the country, which the local prison officials were either unaware of or did not care about.

Going forward, this project will serve as an example for future organizing and litigation in the fight against prison expansion.

While the merits of the lawsuit were never ruled on in court, the lawsuit was a factor in the BOP pulling the Record of Decision. A win is a win and wins are few and far between in prison litigation. However, had the lawsuit moved forward in court, I believe we would have prevailed and it would have made an excellent test case for future litigation. Going forward, this project will serve as an example for future organizing and litigation in the fight against prison expansion. I like to think that for every prison that is not built, that is one less prison that has to be torn down when prison abolition becomes a reality.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.