Amber Williams-King

Black radical love in Waterloo

Between 1820 and 1867, free and formerly enslaved Africans settled the largely unsurveyed area between Waterloo County and Lake Huron. This all-Black community, known as the Queen’s Bush settlement, became home to more than 1,500 Black people.

In The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers 1839–1865, author Linda Brown-Kubisch notes that the residents of the Queen’s Bush settlement relied on “muscle and an axe” to clear the land and build churches, schools, and homes. In addition to the persistent threat of freezing from the cold, Queen’s Bush residents had to ward off attacks from bears and wolves. As they quickly learned, the community quite literally depended on each other for survival.

In the 1850s, after the government surveyed the land, Black settlers could not afford to buy the land they had built their homes on, and the community scattered. But over 170 years since the Queen’s Bush settlement dispersed, a network of African, Caribbean, and Black people continues to build community, share resources, and keep each other safe in the Waterloo Region.

The African, Caribbean, Black (ACB) Network of Waterloo Region has been organizing since 2018, acting as an umbrella group for local activists fighting for Black liberation.

”We stay committed and we stay connected because of this profound, radical love that we have for our communities.”

Individuals and organizations in the Waterloo region have been working to dismantle anti-Black racism in the region for decades. But with no overarching way to connect the region’s Black groups and leaders, activists were often siloed, limiting their capacity and duplicating their efforts.

The ACB Network’s core committee is composed of six people who help build connections among local activists, allowing them to share resources and organize more strategically. Together, they advance a common mission: to fight anti-Black racism; to reduce and remove structural barriers to employment, housing, and health care for Black community members; to highlight local Black-led initiatives; and to develop Black leadership to catalyze a movement for Black liberation in the region.

Connecting Black radicals

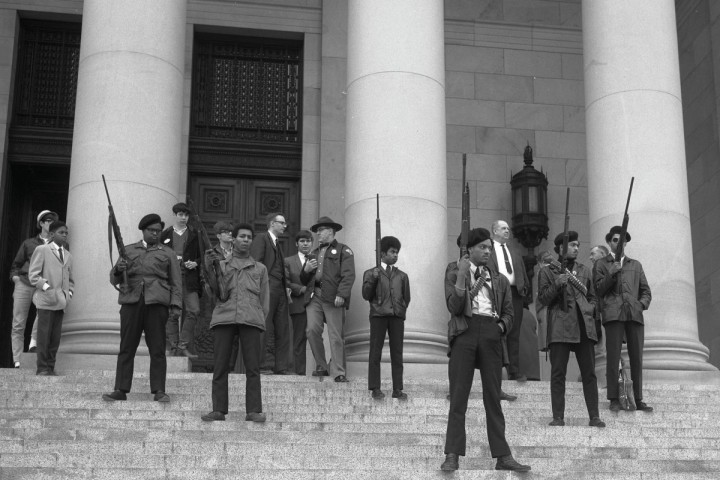

Ruth Cameron (top) and Ann Marie Beals (bottom) sit on the advisory committee of the African, Caribbean, Black Network of Waterloo Region, where they organize to dismantle anti-Black racism and catalyze a movement for Black liberation in the region. Photos by Yeabsera Agonfer.

“Any time he met someone new within the African, Caribbean, or Black community in Waterloo Region, he would reach out to that individual or group and connect with them, and connect people with each other,” she recalls.

Though Thompson no longer lives in Waterloo, Cameron says that the connective tissue formed thanks to his “intentional practice of reaching out” remains with the ACB Network.

Dr. Ciann Wilson, a professor and health researcher with over a decade of experience working with Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities across Canada, also sits on the ACB Network advisory committee. Wilson points out that one of its catalysts was a desire to build on the earlier efforts of Black activists in the region and bring “sustained attention” to the organizations and people who “had a history of essentially doing unpaid mutual aid and community development work.”

Organizing through crisis

In recent years, the ACB Network has set its sights on addressing two crises affecting Waterloo Region’s Black community: health inequities during a deadly global pandemic and an onslaught of police surveillance and violence.

Between July 17 and October 21, 2020, Black people in Waterloo region accounted for 16.7 per cent of local COVID-19 cases – even though they made up less than 3 per cent of the population. The ACB Network put out a statement in February 2021 calling for Public Health in the Waterloo region to take a “health equity approach” to the crisis, which meant prioritizing getting COVID-19 tests and vaccines to poor, racialized communities.

Then, the ACB Network sprang into action: they advocated for COVID-19 testing pop-up clinics, created fact sheets and held Q&A sessions that answered community members’ questions about vaccines, advocated for multilangual campaigns, and partnered with Indigenous-led organizations to bring support and vaccines to those communities. Cameron and the ACB Network also successfully pushed for people with HIV to be prioritized in the first rounds of vaccination.

“The politics that hold us together and allow for the sustainability of the group to continue is a deep love and appreciation for Black people and Black life.”

The network’s efforts to protect the health of Black community members extend beyond COVID, too.

Back in 2016, a local news investigation found that Black people in Waterloo were four times more likely to be stopped and questioned by police than their white counterparts. Little has changed in the intervening years. In November 2021, the Waterloo Catholic District School Board called the police on a four-year-old Nigerian girl, who the board claimed was being violent, sparking uproar from local Black families.

Since the investigation in 2016, the Waterloo Regional Police Service budget has only increased, ballooning from $150.7 million to $214 million. Now, it’s matched by a growing call for police to face more public scrutiny and eat up less public money.

In 2021, the ACB Network joined forces with another Waterloo group, ReAllocateWR, to call for the municipality to reject a proposed $5.2 million increase to the Waterloo Regional Police Service budget. They argued that the police service should be defunded, and its budget redirected to community-led care and safety. The network’s calls to action included more public transit in low-income neighbourhoods; fare-free transit for K–12 students, disabled people, and low-income people during peak hours; community-led mental health supports and responses to violence; inclusive, accessible, and supportive housing; and a Black cultural centre.

“In our discipline of hope, we maintain a vision for new histories, free of policing.”

They were doing this work long before “defund the police” became a common rallying cry. In 2017, when a judge was tasked with investigating police street checks in Ontario, the ACB Network successfully pushed to ensure that Kitchener-Waterloo was included in the study. Similarly, between 2020 and 2021, community pressure from the ACB Network and other community groups led the Waterloo Region District School Board to suspend – and ultimately terminate – the School Resource Officer (SRO) program, which placed uniformed police in select schools under the auspices of “community building.”

While these victories mark major milestones for Black people in Kitchener-Waterloo, they have not come without backlash.

Cameron says that right-wing attacks against LQBTQ community members have followed the decision to terminate the SRO program. “In particular,” Cameron explains, the attacks targeted “trans and gender non-conforming youth and staff at the school board, and particular pockets of queer and trans activism that also are vested in defunding police, due to the violence experienced by LGBTQ communities.”

Radicalism in a small city

“There were times where we were met, I think, with kind of bewilderment because we would state facts,” Cameron recalls, “and this in and of itself was seen as radical, and I have to laugh.”

The ACB Network often names and indicts policing and white supremacy in its public statements. Last February, the group criticized the inclusion of police in Black History Month celebrations, tweeting, “Police are given space to centre their death-dealing institution and collectively wash their reputations during a month intended to focus awareness on Black community. In our discipline of hope, we maintain a vision for new histories, free of policing.”

“If we would state that an incident of violence within another system was unacceptable, people sometimes would act as though that speaking, just speaking, that truth was somehow going to change things,” Cameron explains.

“There is a Black experience. We all get in the white glare. [...] They don’t care if you’re Somali or Eritrean or Jamaican. If you’re getting pulled over, you’re often getting pulled over because phenotypically, you’re Black passing.”

For some members of the community – particularly those who want to “go along to get along” – this kind of language feels too confrontational. Wilson recalls that advancing an explicitly anti-racist approach was challenging for many members of the community, regardless of race.

“I think that not only amongst non-Black but also even the larger Black community, it’s terminology that can be really politicized, right? It’s politically charged, and in some cases polarizing,” she says.

“Folks weren’t sure if they wanted to invoke language around anti-racism or racism at all, when talking about some of those issues in the broader community.”

The ACB Network is careful to note that it does not claim (and never has claimed) to speak for the entire community. But it does the work of building relationships, having difficult conversations, and bringing community members along when they’re ready.

Recognizing the diversity of thought and experience in Waterloo’s racialized communities is something that the network navigates carefully. Even though the terms “African,” “Caribbean,” and “Black” are often conflated, the ACB network uses all three deliberately.

“We are not all able to be lumped into one box. We do a disservice sometimes when we do that, because it does homogenize.

“Many of our continental African brothers and sisters never use that language until they get here. They’re tribally identified or identified by nationhood in the places and spaces that they’re coming from,” Wilson explains. “It’s only when they come here that they have a Black experience, right?”

Wilson’s not interested in flattening the diversity of Waterloo’s communities. “We are not all able to be lumped into one box. We do a disservice sometimes when we do that, because it does homogenize.”

At the same time, she explains, “there is a Black experience. We all get in the white glare. [...] They don’t care if you’re Somali or Eritrean or Jamaican. If you’re getting pulled over, you’re often getting pulled over because phenotypically, you’re Black passing.”

So the network must strike a delicate balance between recognizing the unique needs of the diverse communities that fall under that ACB Network umbrella while maintaining collective pressure on a violent, anti-Black state apparatus.

“Folks weren’t sure if they wanted to invoke language around anti-racism or racism at all, when talking about some of those issues in the broader community.”

It is challenging work made more difficult by the lack of a critical mass of African, Caribbean, and Black people in the region – less than 5 per cent of Waterloo region residents, a total 26,590 people, identified as Black in the 2021 census. This contrasts with bigger cities like Toronto, which is home to 442,015 Black people.

So the network’s sustainability is an ongoing concern. Nevertheless, the ACB Network has materially improved the lives of many Black people in the region and helped shift narratives around defunding the police, economic equality, and health equity through its sustained focus on capacity building, education, and collaboration.

“The politics that hold us together and allow for the sustainability of the group to continue is a deep love and appreciation for Black people and Black life,” Wilson explains.

”We stay committed and we stay connected because of this profound, radical love that we have for our communities.”

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.