The Canadian state and Black disregard

Review of BlackLife: Post-BLM and the Struggle for Freedom

In BlackLife: Post-BLM and the Struggle for Freedom, Rinaldo Walcott and Idil Abdillahi want to change how readers think about Black Canadians. The authors examine Toronto between 1992 and 2005 as a window into Black life. Here, Walcott and Abdillahi coin the term “BlackLife,” arguing that “living Black makes BlackLife inextricable from the mark of its flesh, both historically and in our current time.” Each chapter of BlackLife carefully weaves together analyses of history, philosophy, policy, art, and activism to create a fuller picture of Black Canadian existence.

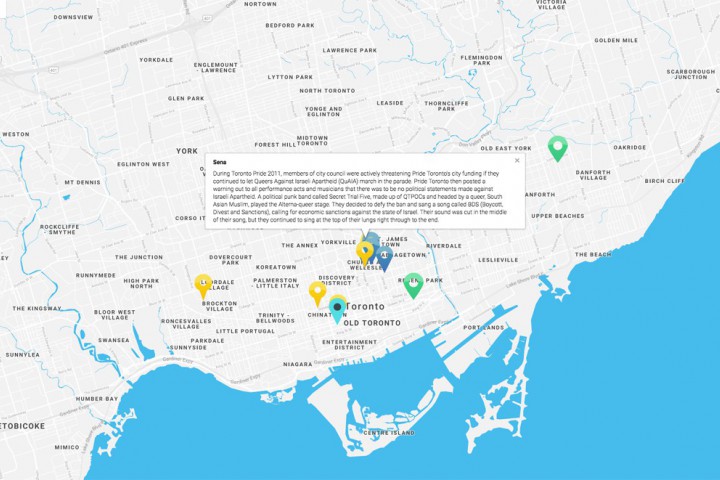

“The 1990s were Black” declare Walcott and Abdillahi, noting that the early 1990s in Canada were marked by unprecedented Black cultural expression in literature, music, theatre, and activism. It was in 1989 that Maestro Fresh Wes’s “Let Your Backbone Slide” became the first Canadian rap song to appear on the Billboard Top 40. It was 1992 when Black people took to the streets in protest of police brutality in the now-famous Yonge Street Riot. It was also in 1992 when Stephen Lewis’ Report on Race Relations in Ontario helped highlight the pervasiveness of anti-Black racism in Ontario. For a while, it seemed that Black people were a central part of a Canadian consciousness.

By 2005, however, things looked different for Black Ontarians. After surviving Ontario premier Mike Harris’s devastating cuts to social services and programs in the late ’90s and early aughts, Black communities in Toronto faced the creation of the Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy (TAVIS), a specialized policing unit that relied heavily upon surveillance and profiling of Black communities. Walcott and Abdillahi argue that 2005 was the year that “firmly cemented Black disregard in the nation-state of Canada.”

To be clear, BlackLife is not a reclamation project aimed at reinstalling Blackness into the nation-state. Instead, it shows that the anti-Blackness at the core of our understanding of the nation and of humanity informs our history, art, policy, and activism – and ultimately constrains our imaginations.

Central to Walcott and Abdillahi’s work is the argument that modernity, ripe with its assertions about what constitutes humanity and humanness, has never considered Black as human. Our existing narratives about Canada – which range from the myth of European colonizers “discovering the new world” to the contemporary notion of Canada as a multicultural utopia – are unified through their refusal to accept BlackLife as a central part of Canadian identity. In this context, Blackness is treated as either non-existent or incidental to the formation of Canada.

To be clear, BlackLife is not a reclamation project aimed at reinstalling Blackness into the nation-state. Instead, it shows that the anti-Blackness at the core of our understanding of the nation and of humanity informs our history, art, policy, and activism – and ultimately constrains our imaginations. The authors highlight the work of Dionne Brand and Austin Clarke as examples of contributions that “rebuke and rewrite the violence and indeed the crimes of European modernity past and present.”

The third and final chapter of BlackLife, “After Black Lives Matter: Black Death, Capitalism and Unfreedom” addresses the plight of Black people under racial capitalism (an analysis of capitalism that understands slavery, colonialism, and imperialism as essential to its nature), zeroing in on the fact that multiculturalism has failed BlackLife. Despite the well-worn myth of Canadian benevolence, Black people continue to be denied access to decisions about policies, procedures, and initiatives designed to better society. This, of course, is evidenced by Black overrepresentation in the child welfare and criminal justice systems, where the proportion of Black children admitted into care is more than twice as high as their proportion of the population, and where 10 per cent of federal inmates are Black, despite Blacks making up only 3 per cent of Canada’s population. The authors assert that “liberal, conservative and left discourses continue to fail Black people, constantly endangering our lives not only in Canada but globally as well.” This assertion steers the book toward its conclusion: that new modes of thinking and engaging are required in order for us to create a new world. Walcott and Abdillahi argue that policies should be scrutinized through the lens of a “Black Test” to determine whether they affirm BlackLife.

Readers frustrated with Toronto serving as the stand-in for Black Canada will once again find themselves on familiar ground.

As this book’s timeline suggests, the authors do not directly engage with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Readers looking for a detailed exploration of the Movement for Black Lives or a critical examination of BLM-Toronto’s actions will find themselves disappointed. This book is not a chronology of events, but rather an exploration of interrelated concepts, ideas, and moments that help define BlackLife. The book’s subtitle, “Post-BLM and the Struggle for Freedom,” is perhaps best described as a call for a shift in world view rather than the declaration of the end of a movement. And readers frustrated with Toronto serving as the stand-in for Black Canada will once again find themselves on familiar ground. While Toronto – home to the largest Black population in Canada – is a necessary case study, examples drawn from across the country would do much to flesh out the slim volume. These concerns, however, do little to detract from a book that skilfully moves across disciplines and geographies to show that BlackLife in Canada is both local and global, historical and contemporary.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.