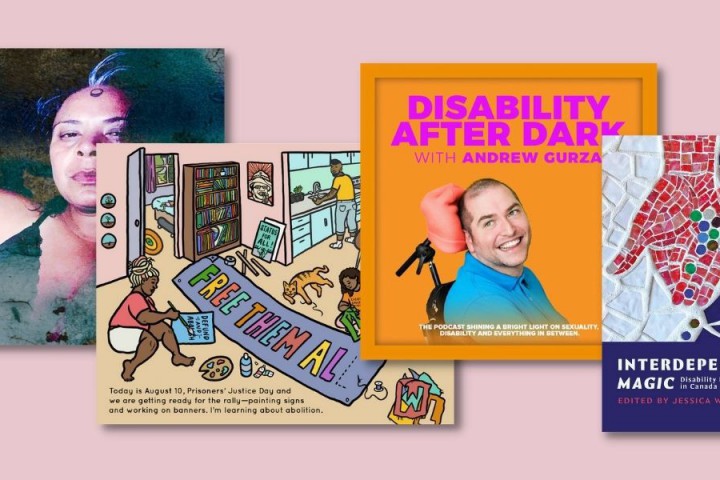

From left to right: Destiny, Mary, Amani, Ahona, and Yasmine.

What is disability justice?

Plain language summary (What is this?)

Briarpatch asked five members of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario’s Youth Action Council (YAC) – Mary, Yasmine, Destiny, Amani, and Ahona – what disability justice means to them:

- “Disability justice means centring the needs, lived experiences, and wisdom of Black, Indigenous, and racialized disabled people,” says Yasmine.

- It means being critical of the systems – like capitalism and colonialism – that profit from making some people disabled, says Destiny.

- “It means we leave space for folks to rest, to move at their own pace, to be angry or sad or sick or depressed,” says Ahona.

- Briarpatch also asked what they see in the future of the movement. They say: 1) an end to racism in mental health systems; 2) working to abolish prisons, long-term care homes, and child welfare, and take care of people without locking them up; and 3) more attention paid to the role of war and Canada’s military in disabling people in poor countries.

This special disability justice issue would not have come together without the hard work and insights of members of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario’s Youth Action Council. Briarpatch asked five YAC members – Mary, Yasmine, Destiny, Amani, and Ahona – what disability justice means to them and what they see as the future of disability justice (DJ) organizing in Canada.

Tell us a little bit about who you are.

Mary: My name is Mary Cep, I’m 22 years old, and I’m currently taking a break from my studies in the social sciences program at McMaster University. I’m passionate about mental health; I like to write, act, sing, and dance. Most of all, I like talking to people about almost anything under the sun. I believe people have incredible stores of knowledge and insight just waiting to be tapped into through open and honest conversation.

Yasmine: My name is Yasmine Simone Gray, I’m 25 years old, and I’m completing a Master of Arts in critical disability Studies at York University.

Destiny: My name is Destiny Pitters and I’m 23 years old. In 2021, I graduated from Wilfrid Laurier University with a degree in English and a double minor in human rights and human diversity and religion and culture. I like participating in grassroots organizing, volunteering, and making art. Most of my work prioritizes serving the southern part of so-called Ontario, primarily Hamilton, Brantford, and the Greater Toronto Area.

Amani: My name is Amani Omar and I’m a 20-year-old artist. My work mostly consists of visual arts and spoken word poetry. I use these mediums to talk about issues like gun violence, Islamophobia, racism, and ableism, as well as radical self-love, to uplift marginalized youth.

Ahona Mehdi

Ahona: My name is Ahona Mehdi, I use she and they pronouns, I’m 19 years old, and I’m based in Hamilton, Ontario. I’m pursuing an Honours Bachelor of Arts in ethics and political philosophy at the University of Ottawa, but I’m looking to transfer to McMaster University to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in social sciences with a specialization in political sciences. I’m also a member of Hamilton Students for Justice (HS4J), a grassroots group of Black, Indigenous, racialized, LGBTQ+, and disabled students fighting for police-free schools, penal abolition, and an education system where students are loved and valued.

Do you identify as disabled?

Destiny: I proudly identify as Black, queer, and disabled, among other things. I’ve never had trouble identifying as disabled because in doing so, I’m pointing a finger back at the institutions that depend on disabling Black, Indigenous, racialized, and poor bodies and minds. By identifying as disabled, I’m asserting that despite their efforts, I will move through this world in ways that are as comfortable, natural, and restorative to me as possible.

Certain communities, particularly those that are Indigenous, racialized, and hailing from the Global South, are more likely to be(come) disabled because our bodies and lands are seen as available for injury through environmental racism, police brutality, war, and labour. The consequences of this violence are carried in our bodies and minds for generations. Since disability is complicated by legacies of racist, colonial violence that affect us to this day, I also honour those who don’t identify as disabled – whether that’s because they’ve seen their disabled peers be punished or ostracized or simply because it’s not a source of pride for them.

Mary: I was diagnosed with ADHD in the fall of 2020 and I’m still struggling to identify as disabled. On one hand, I know that sometimes when I struggle to focus, it could be due to my own indecision and lack of planning. On the other hand, I know that I can’t demand “normal” levels of productivity from myself and expect to be successful in my endeavours with absolutely no difficulty. I have a million ideas running through my head at all times and I start and stop tasks because my brain has less norepinephrine and dopamine than non-ADHD brains. Dopamine and norepinephrine are neurotransmitters that make you feel satisfied when you complete a task. Being deficient in these hormones makes it harder to organize my schedule and to feel fulfilled in doing “normal” everyday things like taking a shower.

The fact that this disability is invisible is why people with ADHD are often called “lazy” or “unfocused.” People can’t see that we have drive, but without medication, guidance, and strategies for decreasing distractions and prolonging focus, everyday tasks become very difficult to complete. I tend to do really well in high-stress situations because the adrenaline forces me to have a singular focus. Being medicated has helped me immensely, but the other half of the battle is continuing to restructure my routines and schedule to allow me to focus and do things I want to do.

Yasmine: Disabled, Mad, and psychiatric survivor are all terms I view as being part of my identity.

Amani Omar

Amani: I started identifying as disabled around 2017, when I realized that it was a term that I could use to describe myself. I’ve been chronically ill my whole life, but the word “disability” is stigmatized in the Somali community and I was chastised for using it growing up. As I have learned more about myself, being disabled has become a key part of my identity.

Ahona: I identify as brown, Muslim, queer, and disabled. I also appreciate the term “neurodivergent,” which refers to all the non-normative ways people process information and engage with themselves and others. Since many of my disabilities are invisible, I would often mask as a kid. “Masking” is the practice of mimicking neurotypical behaviours in social settings as a survival mechanism. Identifying as disabled took a lot of work because only recently have I found spaces like DJNO and HS4J where I could develop a fuller understanding of disability.

I first wondered whether I was disabled when I was 17 years old after Sarah Jama, the co-founder and executive director of DJNO, told me about the opportunity to apply for DJNO’s Youth Action Council. At the time, I didn’t know that I could identify as disabled, and I began to unpack my understanding of disability. I spent a lot of time reading the book Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. Many of the passages and excerpts deeply resonated with me, including this one Piepzna-Samarasinha quoted from Yashna Maya Padamsee’s blog: “Too often self-care in our organizational cultures gets translated to our individual responsibility to leave work early, go home – alone – and go take a bath, go to the gym, eat some food and go to sleep. So we do all of that ‘self-care’ to return to organizational cultures where we reproduce the systems we are trying to break.” This reflected my experience of having needs that were opposite to the neurotypicals and ableds around me, and it allowed me to dismantle my colonized understanding of disability. Reading these words from a fellow brown queer femme allowed me to challenge internalized ableist narratives of individual responsibility and see care as a collective practice and responsibility.

"I’ve never had trouble identifying as disabled because in doing so, I’m pointing a finger back at the institutions that depend on disabling Black, Indigenous, racialized, and poor bodies and minds."

What is your understanding of disability justice?

Yasmine: Disability justice means centring the needs, lived experiences, and wisdom of Black, Indigenous, and racialized disabled people. As a disability studies scholar, I’ve seen first-hand how the default disabled subject is presumed to be a white, cisgender, formerly able-bodied, heterosexual man. That means that the priorities of disability rights don’t always reflect the needs of people who are marginalized through race, gender, sexuality, and class. Disability justice looks at that narrow lens and says: “Hey! Don’t overlook disabled people who are experiencing multiple intersecting and layered forms of oppression at the same time. We matter too and you can learn a lot from our analysis and understanding of the world.”

Destiny Pitters

Destiny: Disability justice goes beyond rights granted by a state that simply aim to incorporate disabled folks into capitalist and colonial systems and institutions. Disability justice is about being unflinchingly critical of disabling and debilitating systems like capitalism and colonialism, instead imagining a future where we’re all taken care of and we all show up for each other, and then practising that right now – whether it’s talking to your neighbours, crowdfunding, or care-mongering. The disability justice movement is one of the most holistic, intersectional movements out there because it is inherently anti-racist, queer- and trans-centred, a critical evaluation of the status quo, and makes space for us to be our whole selves.

Amani: Disability justice is about understanding that our human differences are essential to better understanding and helping one another move forward in the world. Disability justice values access for all and also compassion. The only way we as a society can thrive is by uplifting each other and dismantling systems that have been built with nothing but profit in mind. It’s about putting people’s needs first rather than lining the pockets of the rich.

Ahona: Disability justice is the practice of loving one another, even if we’ve never met. DJ understands that we can’t continue to leave each other behind. In the DJ movement, we’re not only challenging and dismantling ableist institutions and systems but building a future founded on mutual aid, community care, and accessibility – all fierce acts of resistance. Ableism is grounded in white, settler colonial ways of knowing that consider disabled people to be “defective” and “abnormal.” Instead, disability justice understands that ableism comes from the enslavement, neglect, and genocide of Black, brown, and Indigenous minds and bodies.

Disability justice has become a buzz-word that gets thrown around in social justice circles, and many people that use it fail to truly understand and respect the principles of disability justice. Disability justice is not about ideas of self-care – like bubble baths, dieting, or training to run a marathon – but collective care. It’s rooted in the understanding that refusing to conform to capitalistic ideals of productivity and normativity is deviant, love-fuelled resistance. It means we leave space for folks to rest, to move at their own pace, to be angry or sad or sick or depressed. It’s building toward a world wherein we don’t have to mask or be “easy to deal with” to be loved and valued.

How has being part of DJNO’s Youth Action Council transformed you, and what has it allowed you to do?

Mary Cep

Mary: The YAC has provided me with guidance and assistance as I learn more about my own disability and relieved some of the pressure to fit in and be “normal.” Connecting with other disabled people has shown me what’s possible when we come together, empower one another, and allow people to show up as themselves – everyone’s star power shines through.

Destiny: Being a part of DJNO has been so exciting for me! To be able to connect and organize with fellow racialized disabled folks, call out harm in our city, and work on projects supporting disability justice research and action has been so nourishing. Currently, I’m working with others on a research project about the experiences of racialized and disabled prisoners, whose perspectives are woefully lacking in mainstream conversations and are critical for any kind of organizing around prison justice.

Ahona: Being part of the YAC has created so much space for me to explore and better understand my own disabilities, while learning with and following the lead of disabled trailblazers in so-called Canada. Working with Black, queer, trans, Mad, neurodivergent, and disabled youth has opened so many doors for challenging institutional, systemic, interpersonal, and internalized ableism in all facets of life – something I am endlessly grateful for.

What do you find to be most exciting or promising about disability justice activism in Canada? What would you like to see come to the forefront?

Yasmine Simone Gray

Yasmine: Let’s be more critical about medical racism in the mental health system. Let’s get serious about abolition of prisons, jails, long-term care homes, and child welfare. We need advocates to develop a deep understanding for intersectionality and cross-movement solidarity. We can only achieve disability justice if we’re simultaneously working to promote racial justice, environmental justice, abolition, and other justice and freedom movements. We have to make these connections if we’re going to build and maintain a strong movement that leaves no one behind.

Destiny: What I find promising is that since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been more mainstream discussions about disability justice, whether or not people refer to it as such. Many COVID policies have harmed and failed disabled people, like prematurely lifting mask mandates, a lack of investment in ventilation, and vaccine hoarding by the Global North. At the same time, we’ve implemented accommodations like working from home that disabled people have been calling for for years. I fear that as we move into “post-pandemic” discourse, the lessons and outrage will be lost. I hope we learn from the last three years and invest in public health care, increase social assistance to match the cost of living, and amplify the voices of disabled peoples in conversations about health care.

I’d like to see more attention paid to the relationship between militarism, war, and disability. BIPOC and those in the Global South experience ongoing imperial violence in which Canadians are complicit, including disabled Canadians. I appreciate the work that the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute is doing, uncovering Canada’s role in war, extractivism, and the arms trade abroad, which is framed as diplomacy, aid, and intelligence by the federal government. I think disability justice demands that we acknowledge the debilitating harms of Canadian imperial violence – like Canada’s arms exports to Israel that facilitate attacks on Palestinians or the destruction caused by Canadian mining companies in the Global South – and advocate alongside all those targeted. I hope to witness an increased response to Canadian militarism and imperialism from disability justice groups.

Ahona: Disability justice activism in so-called Canada is beyond promising – especially because it is being led by Black, Indigenous, and racialized disabled folks. Our movements are rooted in mutual aid, education, and accessibility, while simultaneously working to dismantle ableist systems like policing, prisons, and long-term care facilities, which target and confine disabled people. Some examples of disability justice champions include the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project, which advocates for the abolition of sites of incarceration and for the well-being of prisoners; the Hamilton Encampment Support Network, which supports houseless and unhoused Hamilton residents; and Doctors for Justice in Long-Term Care, a group of physicians advocating for safe living conditions for long-term care residents.

The goal of the disability justice movement is penal abolition. We see this in the fight to decarcerate so-called Canada, to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline, and to abolish all carceral systems including long-term care homes, prisons, and psychiatric wards. The work is being done in countless capacities, from youth to seniors, to health-care workers, to unhoused folks, and we know that we will win.

Readers like you keep Briarpatch alive and thriving. Subscribe today to support fiercely independent journalism.

_720_480_90_s_c1.jpg)